There’s a square cutout in my sidewalk intended to be used as an herb garden. In past years it has yielded lush basil plants and a tomato plant that took over the world. This past spring, between travel schedules, I planted a few marigolds in there and left it to its own devices. Conducting a long-overdue weeding, later in the summer, I discovered that a plant with little black berries on it had found a foothold near the marigolds. American black nightshade. Poison in my garden space.

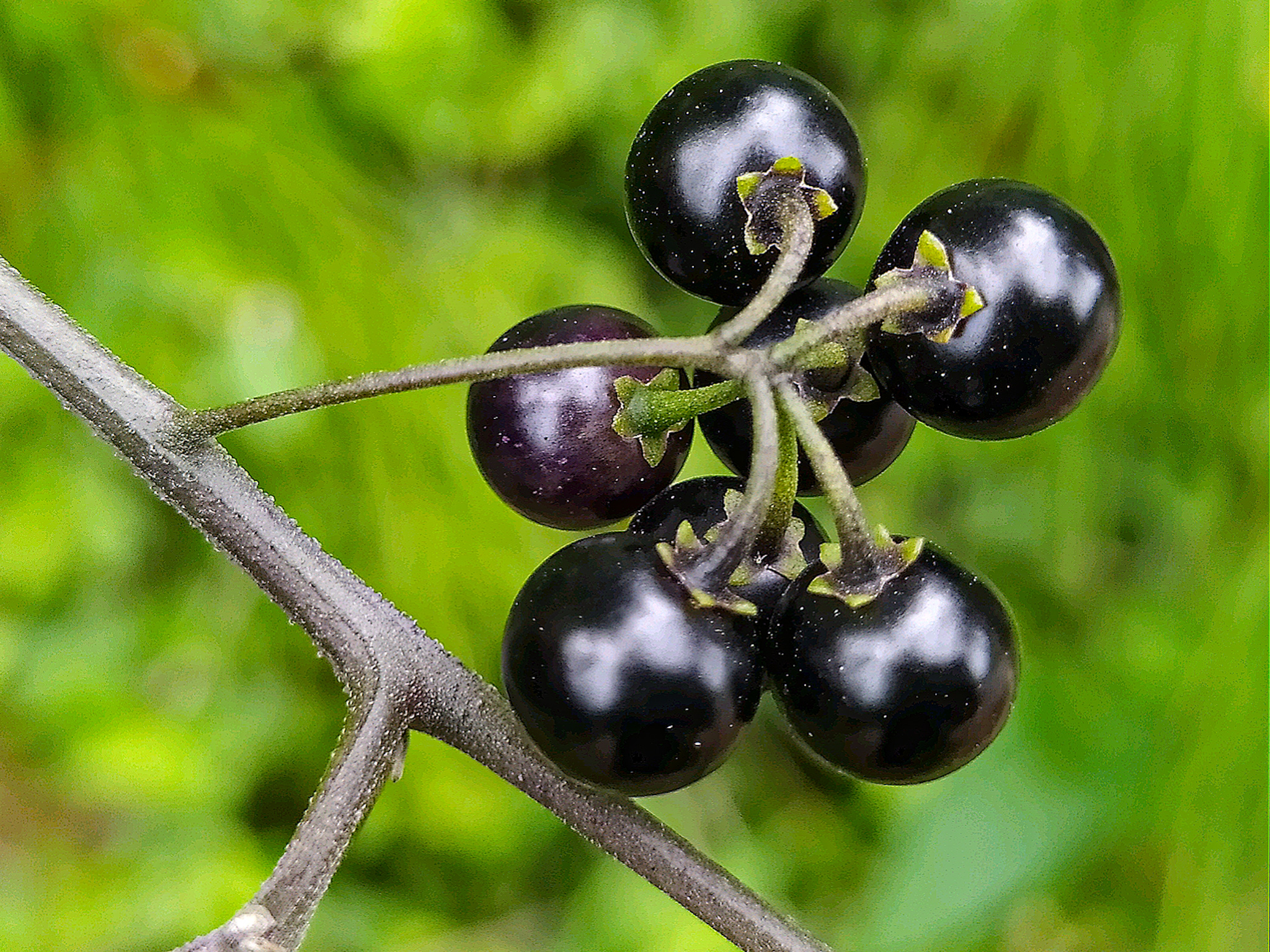

The nightshade family, Solanaceae, includes such familiar plants as tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, eggplant and tobacco. It also includes several species of poisonous nightshade plants, including the American black nightshade, (Solanum americanum). Earlier in the summer, this foot-tall plant with its multiple branching stems was festooned with clusters of little white flowers. Now where those flowers were are clusters of little shiny black berries. Each of these berries contains up to 120 flattened seeds. And each of these berries and leaves and stems and roots, indeed the entire plant is poisonous to humans and livestock. Eating any part of the plant can cause severe vomiting, nausea, salivation, drowsiness, abdominal pain, diarrhea, weakness, respiratory depression, convulsions, hallucinations, and death.

Birds don’t seem to be affected by the poison though, and many birds, including ruffed grouse, wild turkey, eastern meadowlark, gray catbird, and swamp sparrow are attracted to the berries. Raccoons, striped skunks, white-tailed deer and small rodents also eat the berries, probably not in quantities sufficient to make them sick. The seeds remain viable as they pass through the various digestive systems, so the birds and animals help spread the nightshade across their ranges.

American black nightshade is native to the Americas and is not as lethal as the European nightshade known as belladonna (Atropa belladonna) that probably killed both Roman Emperors Claudius and Augustus as well as McBeth. What a nasty way to go! Roman soldiers also used it to coat their arrowheads, intending to poison their enemies. During the Renaissance, women of fashion believed they would be more beautiful if their eyes were slightly dilated. Belladonna contains atropine, so using it achieved the desired result. They also rubbed it on their skin to bring out the color in their cheeks. Knowing how poisonous nightshade is, mothers were said to have warned their children that if they ate the berries, they would meet the devil.

Today champions of nightshade avow its benefits in small controlled doses for stomach irritation, cramps, spasms, pain and nervousness. They also say that applying poultices of the leaves to the skin helps with psoriasis, hemorrhoids, and deep skin infections.

When I was a little girl, every time I went to the eye doctor he used atropine to dilate my eyes. It didn’t make me into a beautiful Renaissance lady. It made me very cranky. However, it was standard practice in those days. Atropine was also incorporated into over-the-counter belladonna plasters used for rheumatism and pulmonary tuberculosis in the 1950s. Another compound, scopolamine, found in nightshade is still used to prevent motion sickness or nausea after surgery.

Medicine or poison, healing or death. A double-edge sword like so many things in life. Fortunately, the American black nightshade in my garden isn’t nearly as poisonous as the belladonna. I’ll get rid of it anyway.

Photo by: Filo (Wikimedia Commons). Alt text: Close-up cluster of 7 shiny black berries hanging from a single stem. American Black Nightshade.