It’s winter, so it’s not very hard to imagine ice and snow on Owl Acres. But it is hard to imagine thousands of feet of it, compressed into a gigantic glacier that stretches from here back north to the north pole. That’s what Owl Acres looked like though some 2.3 million years ago when the ice age put most of Iowa into the deep freeze.

For reasons still debated, about 2.3 million years ago, the earth’s temperatures cooled, plunging Owl Acres and the rest of the world into an ice age. At least four times over the next two million years, glaciers formed in the Canadian Arctic and bulldozed their way south and west. They reached as far as Owl Acres, and covered most of Iowa at one time or another. Between these major glacial periods, things warmed up for interglacial phases, with temperatures similar to what we have today.

Just imagine a giant mass of ice so heavy that it spreads under its own weight. It moves inexorably across the land. Whenever it encounters obstacles like boulders, it rolls over them, sucking them in, freezing the rocks into place, grinding them to gravel, and generally making them components of the glacier known as glacial drift. The glacier scours the land flat, moving masses of rock and other debris thousands of miles and exposing the limestone and sandstone foundations in its path. Eventually it reaches Owl Acres and further south almost to St. Louis where it’s warmer, and it starts to melt. As it melts, it leaves the glacial drift it was carrying lying in a jumble on the otherwise flat land. As the glacier retreats, streams of water form rivers through the chaos of boulders, rocks, gravel, dirt and clay.

Meanwhile, erosion, a permanent and inexorable factor in earth’s landscaping, begins wearing down the Rocky Mountains and all other exposed rock. This erosion creates a gritty dust called loess. The loess is light enough to be moved by the wind and rain. Prevailing winds from the west pick up this loess and blow it in massive dust storms into the great plains and onto Owl Acres. The loess covers the chaos left behind by the glacier, and, as the climate warms, grasses begin to grow in the loess.

And then the next glacier comes along, shoving much of the loess and the underlying boulders and rocks ahead of it, filling in some stream beds, carving out others, erasing some, but not all, of the records in the rocks left behind over millions of years.

Owl Acres and the surrounding country were ground flat by the second major glacier to cover Iowa, and left strewn with glacial debris. Loess continued to blow into Iowa from the west, covering the glacial drift in a thick layer of soil. Unaffected by subsequent glaciers, this layer of what would become rich prairie soil built up to some 55 feet thick on Owl Acres. Below the layers of silt and clay formed by the Loess, layers of shale, soapstone and slate lead down to veins of coal. The shale, slate and coal predate the glaciers, having formed during the carboniferous period some 300 million years ago.

The last of the four major glaciers to enter Iowa created what’s known as the Des Moines Lobe, a flattened landscape that reaches into the middle of the state. It missed Owl Acres by some 12 miles to the northwest.

This last glacier began to withdraw as the climate started warming again some 13 thousand years ago.

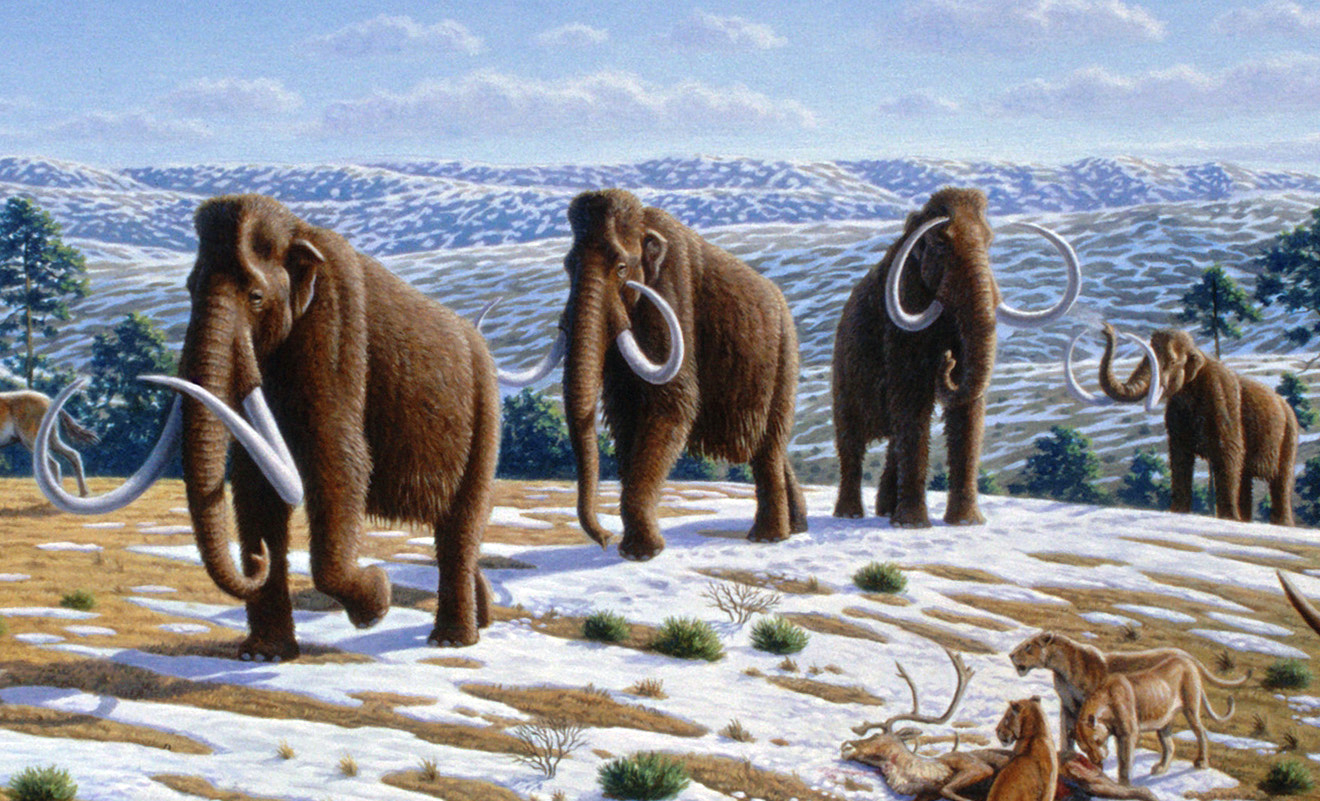

During this glacial deep-freeze and its alternating warm spells, evolution continued apace, resulting in cold-weather animals like mastodons, woolly mammoths, and giant beavers. Grasses evolved to cover the semi-arid interior of the continent. The prairies began to emerge, adding yet more layers to the earth beneath my feet.

1 comment

The best explanation of glaciation I’ve ever received. Thanks, Karen!