The Meskwaki and Sauk tribes lived in Iowa during a period from about 1735 to 1845. They established villages on the Iowa and Des Moines rivers and hunted across Iowa. The eight acres that comprise Owl Acres today would have been a tiny part of the millions of acres they claimed as their hunting grounds at the beginning of this period. However, they had their origins in the woodlands of northeastern Canada. As they were forced to move time and again by the French and their allies, they kept their woodland culture intact. “We are woodland Indians,” said a docent at the Meskwaki Cultural Center and Museum recently. “We are not desert Indians. We are not plains Indians. We are woodland Indians.” As woodland Indians originating in northeastern Canada, the Meskwaki developed strategies for surviving hot summers and brutally cold winters.

In the summer, from approximately May to September, they congregated in large villages located on major rivers. They built relatively permanent long houses which were shared by extended family groups and returned to year after year. They oriented each long house east to west with doors at the narrow ends. Built like a pole building, the house was about 20 feet wide and 40 to 60 feet long. To build them, the woodland Indians set poles in a regular pattern and tied them together with cross members, forming a lattice of squares. They constructed gabled roofs with a ridge pole in the center and covered the entire frame with bark.

Inside, around the perimeter they built waist-high benches used for sleeping at night and sitting or working in the daytime. They often built a second loft level for the younger members to sleep on and to use for storage. Food bundles were hung from the rafters. Women made mats woven from bull rushes which they used as room dividers, separating family groups.

Woodland Indians built their long houses in rows around a central space, housing up to 200 family units. They used the center space for ceremonies, dancing, races and games. Women planted gardens near the perimeter of the village and grew squash, pumpkin, corn and beans. The women also foraged for nuts, berries, edible roots and fruits. The men hunted and fished, using hooks, lines, nets, traps, spears, and arrows. After harvesting and drying their crops, they stored a portion in underground caches and prepared the rest to take with them to their winter camps.

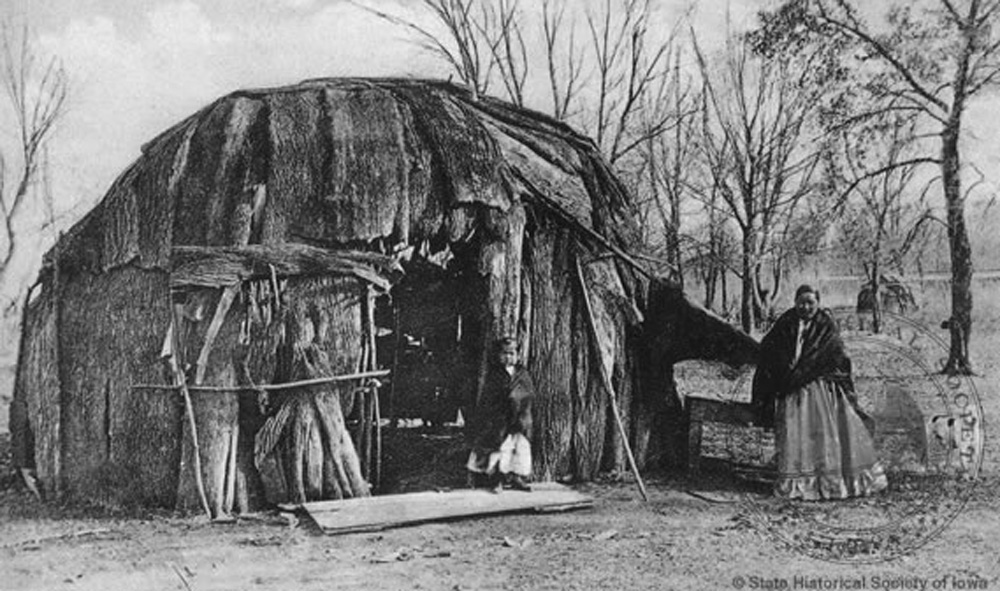

In September or October, the villagers divided into family groups and moved to their winter camps. Often, they established these camps in valleys on smaller streams. The valleys provided some shelter from winter winds, and streams provided a water source and wood from the trees growing along the stream. Instead of the large long houses of the summer village, they built three or four wickiups. To build these dome-shaped structures, they drove poles into the ground in a circle, bending them to form a dome, and tied overlapping poles together at the top. The result was a round structure about 12 feet high with a domed roof. It was designed to shed the heavy snows of the northern winters. Across the poles, from ankle to above head height, they lashed saplings with bark fiber to form a frame of squares that stabilized the structure. They covered this frame with overlapping mats that the women made by weaving cattails. Thus, they an interior space of 10 to 16 feet in diameter.

On the inside, they covered the walls and floors with mats woven of bulrushes. On the floor, they laid buffalo robes, and they hung a bear skin to serve as a door. In the middle of the floor, they constructed a fire ring, and the smoke exited through a smoke hole at the top.

A family would live in the wickiups during the coldest part of winter, telling stories and working on baskets, clothing, tools and similar hand work.

They had a loomless weaving technique that reminded me of lacemaking. Using a variety of natural fibers, including the inner bark of basswood, cedar and slippery elm trees as well as dogbane, milkweed, nettle and other plant fibers. they would attach the fibers to a peeled stick and attach the stick to something solid like a tree. Then, using their fingers, the women would weave a variety of patterns, keeping the weaving taut as they worked. Patterns might be stripes, diagonals, diamonds, squares, zigzags or arrowheads. The woven articles were often used as ceremonial sashes or belts. The men hunted throughout the winter.

The Meskwaki and the Sauk tribes carried these traditions with them from northeastern Canada into Iowa as they were pushed farther and farther away from their ancestral land. A denizen of the neighborhood where Owl Acres stands today declared that as late as 1915, the Meskwaki set up winter camps on the nearby South Skunk River and Indian Creek, one of its tributaries.

Photo by State Historical Society of Iowa

2 comments

Love this!!!! Fantastic information.

So much more to tell–fascinating all around. Thanks.