At the time that Owl Acres was settled, a source of power beyond the physical manual strength of human beings, was needed to achieve the goal of hauling households across the prairie and then breaking the sod to create farms.

The industrial revolution in the 1800s brought a new mindset to people who had hard physical labor to do, like farmers. Breaking sod, planting, cultivating and harvesting were all back-breaking work. It took much too long and was much too hard for long-term sustainability. You couldn’t just go after it was a shovel or a spade. Why not find ways to have machines do the work? Machines were being invented like the John Deere plow and the threshing machine, but they needed “brute strength” to power them.

Enter the ox.

Oxen are essentially just cattle. They were almost always castrated males known as steers. They became oxen by being trained to pull a wagon or a plow. Oxen were used to pull 50 to 75 percent of the wagons on the Oregon Trail.

It took an average of four years of careful training to develop an ox. They learned to respond to verbal commands like gee and haw, and to hand signals. By the time they were trained, the oxen would have reached their adult size and strength. and could be yoked to a wagon or a plow.

On the early frontier, oxen had several advantages over horses. First, they were stronger, more heavily built, and able to work long hours. An ox could pull its own weight, from 1500 to 2500 pounds, and keep going for hours at a time.

Another reason that oxen performed better than horses on cross-country travel was the fact that cattle can eat and process a wide variety of rough forage. As ruminants domestic cattle have a four-chambered stomach where food is processed. The first chamber is the rumen. It is a holding tank where fermentation occurs, breaking down the forage and harvesting energy from the process. As it breaks down, the food moves to the second chamber called the reticulum. This acts as a sort of filter, allowing fine particles of food to move on to the next phase and sending larger particles back into the rumen for more processing. The third chamber is the omasum where more processing happens before the food reaches the abomasum, which is more like the stomach in non-ruminants. After it passes through the stomach, food is processed in the intestines. All this pre-processing in the first three chambers of the digestive system along with chewing a cud, allows cattle to digest tough forage plants that a horse can’t eat.

Oxen could go longer between watering, too, since their rumen held up to 25 gallons of water that they could draw on if needed.

Financially speaking, oxen were a better deal than horses. In the mid-1800s, a horse would cost up to $150 whereas a team of oxen would cost the farmer about $50. Maintenance was cheaper, too. The farmer could make and repair the ox yoke and harness with standard tools, but harness for a team of horses required different tools and were harder to make and repair.

Oxen could work with or without shoes and were less likely to develop foot problems. Their cloven hooves also expanded to help them grip muddy stream banks.

Breeds of cattle, including oxen, during the middle and late 1800s were usually short horns brought from the east, or long horns from the southwest. Either way, the horns were usually left intact because the oxen were harnessed in such a way that the horns could be used to slow or brake a load on steep downhills.

The downside of using a team of oxen was that oxen are slow. A team of oxen pulling a wagon across the prairies would average about 1.5 miles an hour. Horses and mules were faster but less able to cope with deep mud. Oxen don’t sweat like horses do either. Instead, they cool themselves through their breathing. One serious hazard to oxen working hard was that their nostrils would get clogged with dust. If not cleaned out regularly, the dust would suffocate them.

It’s very likely that the first settlers on Owl Acres used oxen to pull their wagons and their plows. By 1890 when Owl Acres was bought by the Dammeier brothers, the sentiment had shifted. Oxen were too slow and too old-school to pull the emerging farm machinery. Horsepower was in. Oxen were out. Horses had replaced the majority of oxen as draft animals, and horses were being bred for the work.

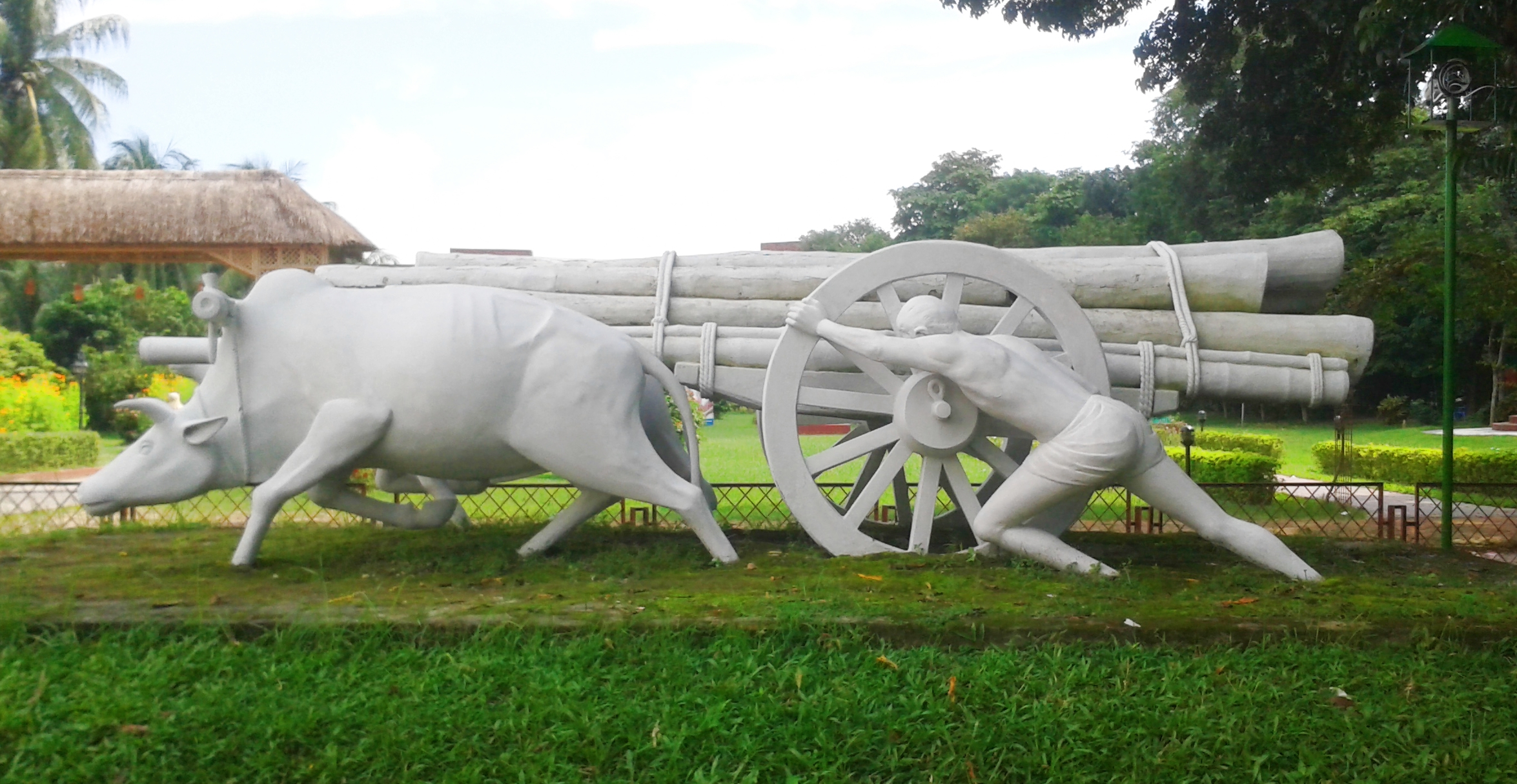

Attribution for this photo is complicated. The picture itself was taken from Wikimedia.org by Masum-al-hasan, who gets the attribution for the purpose of this blog post.

This picture is one of at least 42 images of the same subject on Wikimedia Commons.

The photo is of a sculpture based on a painting. A pair of large cattle with long horns and prominent neck humps, struggles to pull a heavy cart loaded with logs. A shirtless man strains to assist the oxen by pushing on the spokes of the cart’s wooden wheels. The painting and the sculpture are in museum(s) in Bangladesh.

The painter was Bangladeshi artist Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin. Shilpacharya is world renowned for his paintings on famines, most famously of the 1940s. He led the modern art movement in Bangladesh and he is called ‘the father of Bangladeshi modern art.’ He was the founding principal of the Dhaka University’s Institute of Fine Arts, formerly the Government Institute of Arts and Crafts, founded in 1948. The great artist was born in Mymensingh district, near the river Brahmaputra, in 1914. Two of his most famous creations are ‘Sangram’ (‘Struggle,’ the inspiration for the sculpture) and ‘Famine 1943’.

Interestingly, as of press time, we have yet to figure out who created the sculpture. Perhaps some of our esteemed readers might help with the research?