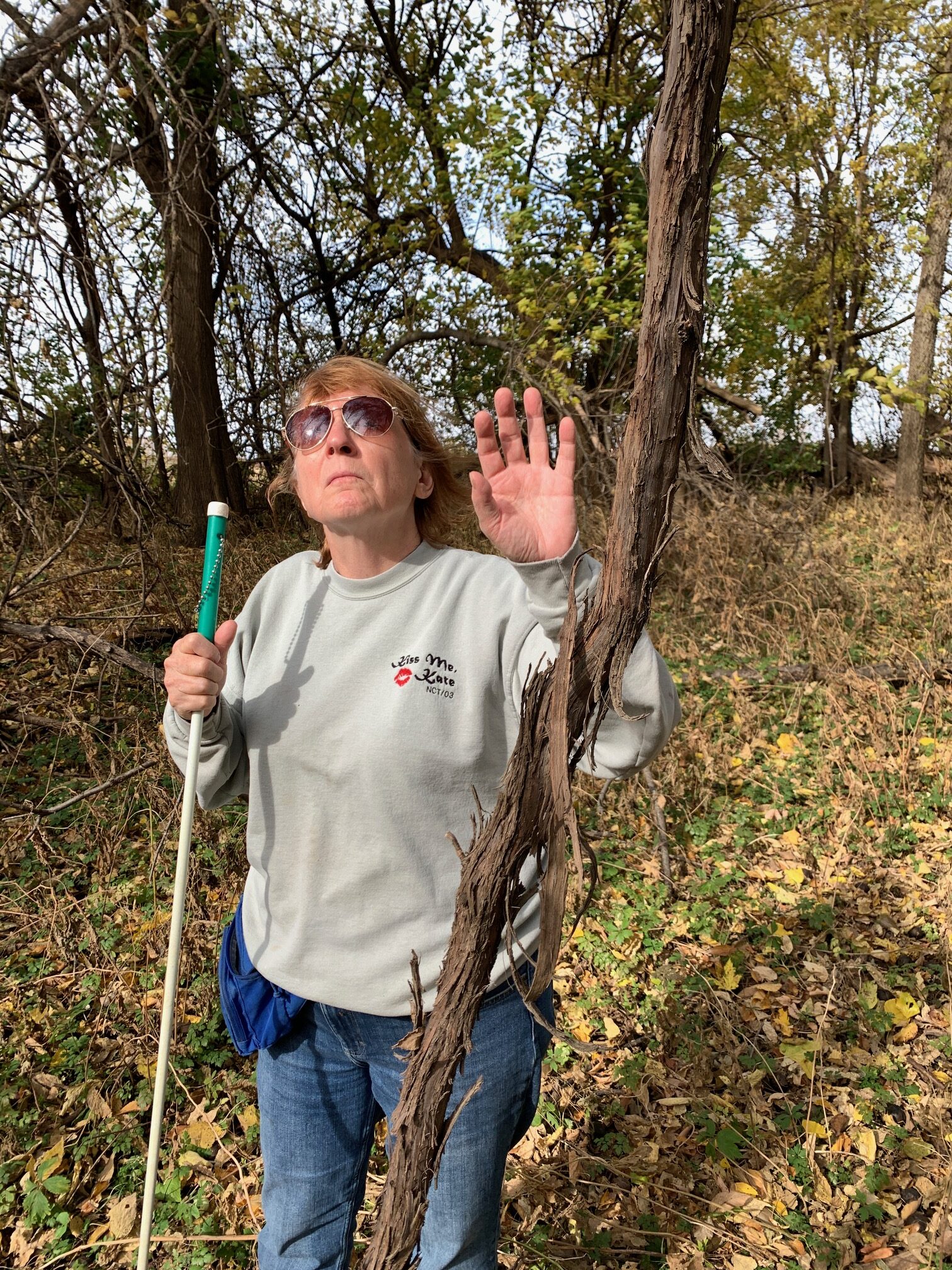

On a lovely Indian summer day in late October, we took a walk through the woods on Owl Acres. Most of the leaves had fallen from the trees, and the undergrowth was dry and crackly. Along with the boxelder trees, hackberries, wild cherry and walnut trees in the woods, some inch-thick woody vines climbed from the ground to points high in the tree canopy. One vine had a shaggy woody bark that peeled off in strips. We guessed it to be a river grape. Its leaves had turned yellow and fallen off just like the tree it was clinging to, so we didn’t have those for identification. But based on the bark, we assumed it to be a river grape (Vitis riparia). It was hanging onto a boxelder tree with a series of tendrils reaching out from the vine.

River grape is native to North America and, like its name suggests, it often grows along the banks of streams. It is also happy, though, to grow in ravines such as the one in the woods on Owl Acres, where the ground is moist.

In spring, river grape vines put out leaves along the vine. The leaves start out yellowish but soon become glossy green. Their edges are deeply toothed, with reddish petioles or stems. They’re four to six inches both long and wide. Little spikes of flowers in spring will create hanging clusters of little wild grapes in the fall. Each one will contain up to four seeds. They taste sweet, and can make nice jelly if you collect a lot of them.

Like other native plants, river grape has its pests, and it also has its methods for attacking them. Two specific types of pests cause the plant to create galls on its leaves. A gall is a growth on the leaf or stem engineered by the plant. The plant creates a gall specifically to surround a pest. For example, the little midge called (Cecidomyia viticola) lays her eggs on a leaf. The plant wants to protect itself from the midge larvae so they don’t defoliate the plant. So the plant grows a lump of tissue that surrounds the eggs. When the eggs hatch, the larvae live in the gall until they’re ready to pupate. Then they bore a hole to the outside, drop off and burrow into the soil where they pupate and emerge as adults. This keeps the larvae contained so it doesn’t cause much damage to the leaves., but it also gives the larvae a protected, food-filled place to grow until it pupates. In the case of these midges, the galls on the leaves don’t damage the plant. They’re just the cost of doing business.

Another pest, however, called a grape Phylloxera (Dactylosphaera vitifoliae) has a story to tell. This little yellow aphid-like insect sucks the juice out of the roots of the grapevine. An infestation will girdle the roots and kill them, stunting or killing the plant. In the case of the river grape and other native species, the plants have evolved a method for attacking the phylloxera. They exude a sticky sap from the roots that traps the insects. And if these little suckers attack the leaves, they are walled off in warty little galls where they don’t do much damage. American grapes evolved along with these pests, and have effective defenses against them. European grapes, however, did not, so when they were accidently introduced to England in the 1850s, they promptly killed off the British grapes. Then they moved to the continent, where they did their damage, so by 1889 two-thirds of all the vineyards in Europe had been destroyed and wine production was cut by 57% in France alone. Horror of horrors! What to do? Americans to the rescue. (It was an American pest, so perhaps its only fitting that an American figured out how to deal with it in Europe.) C.V. Riley was a renowned U.S. entomologist. He noticed that American grape plants could be infested but not killed by the pest, and that if the American grape was used as the rootstock with European varietals grafted onto it, they could get the same wines and survive the phylloxera. Hurray—French wines again!

Back in the woods on Owl Acres, if the midges and the phylloxera are present, they’ve prepared for winter and will resume the battle with the grapevine next spring.

Photo by Author. Alt text: Karen is in the woods behind the house on a bright fall day. The trees have dropped most of their leaves. A large woody vine rises from bottom to top clear through the frame. It’s the main stem of a river grape, its branches and foliage tangled high overhead in the nearby tree.