On a human scale, we think of the size of creatures populating the earth as ranging from gnats to whales. The ecosystem in the soil has a comparable scale, with creatures ranging from the tiniest virus to large digging mammals. Scientists divide them into groups depending on their size—micro (tiny), meso (middle-sized), or macro, the big guys. We’ve looked at the microbes—the tiniest life forms we know of. Now let’s look at the microfauna, the smallest animals that live down there.

The microfauna are the tiniest, and yet they are bigger than the micro-organisms we looked at earlier—the viruses, bacteria, fungi and archaea. The division into groups is a bit arbitrary and is based on body size. We’ll talk about four main groups—protists (which I learned to call protozoa back in the day), nematodes, tardigrades and rotifers.

Remember that some of the spaces in the soil are filled with water, and some of the clumps of dirt have films of water adhered to them. This is where these tiny fellows live—in the water that’s in the soil.

Protists are in their own kingdom, there are so many of them—50,000 species and counting. They are single-celled organisms much bigger than the bacteria and archaea. They are actually aquatic and have to live in the water. Even seemingly dry soil can contain enough water to support a thriving population of protists. When things dry up, or when the salt content of the water reaches a certain point, protists can’t function. Instead, they enter a resting state, or build a wall around themselves and wait for things to change.

When conditions are good, protists eat a lot of bacteria. Some can eat up to six times their own weight in bacteria in a feeding session. Many types of protists are amoebas. They are one-celled, and they can change their shape. They might encircle a bacterium, for instance, and then pull it inside. They might create a tiny bit like a feeding tube that they can push into tiny places to get at bacteria. They eat other things, too, like fungi, other protists, cyanobacteria, algae and even multicellular soil dwellers. Other protists excrete enzymes that break down dead plant material, and once it’s liquified, they absorb it for food.

In a gram of dry soil, you might find from ten thousand to ten million protists. They’re most abundant in the upper layers of soil and around plant roots.

Another type of microfauna living in water-filled spaces or water films is the nematode. Nematodes are classified in the kingdom animalia, and have an entire phylum dedicated to them because they are found everywhere in such large numbers and diversity. Nematodes are tiny roundworms that live in most environments. The ones that live in the soil on Owl Acres may number in the millions per square yard of soil. They live mostly in the top few inches of soil. They are small enough to move through tiny spaces in their environment, excreting slime as they go to ease their passage. Most nematodes are parasites, infesting plants and animals. They can cause serious crop damage by infesting the roots or by poking their stylets into the root cells and sucking out the contents. Others eat bacteria, dead plant material, fungi and other nematodes.

Some 80,000 and counting species have been identified worldwide, and around 230 species may live on Owl Acres. They need a moist soil, and when it gets too dry, they migrate to wetter spots. When that fails, they go dormant, coiling their bodies and ceasing all activity. Many species can be resuscitated after years of dormancy.

Nematodes have their enemies, too. Over a hundred species of fungi trap nematodes in sticky traps, capture them in constricting rings, or paralyze them with poison and then engulf them in strands of fungus.

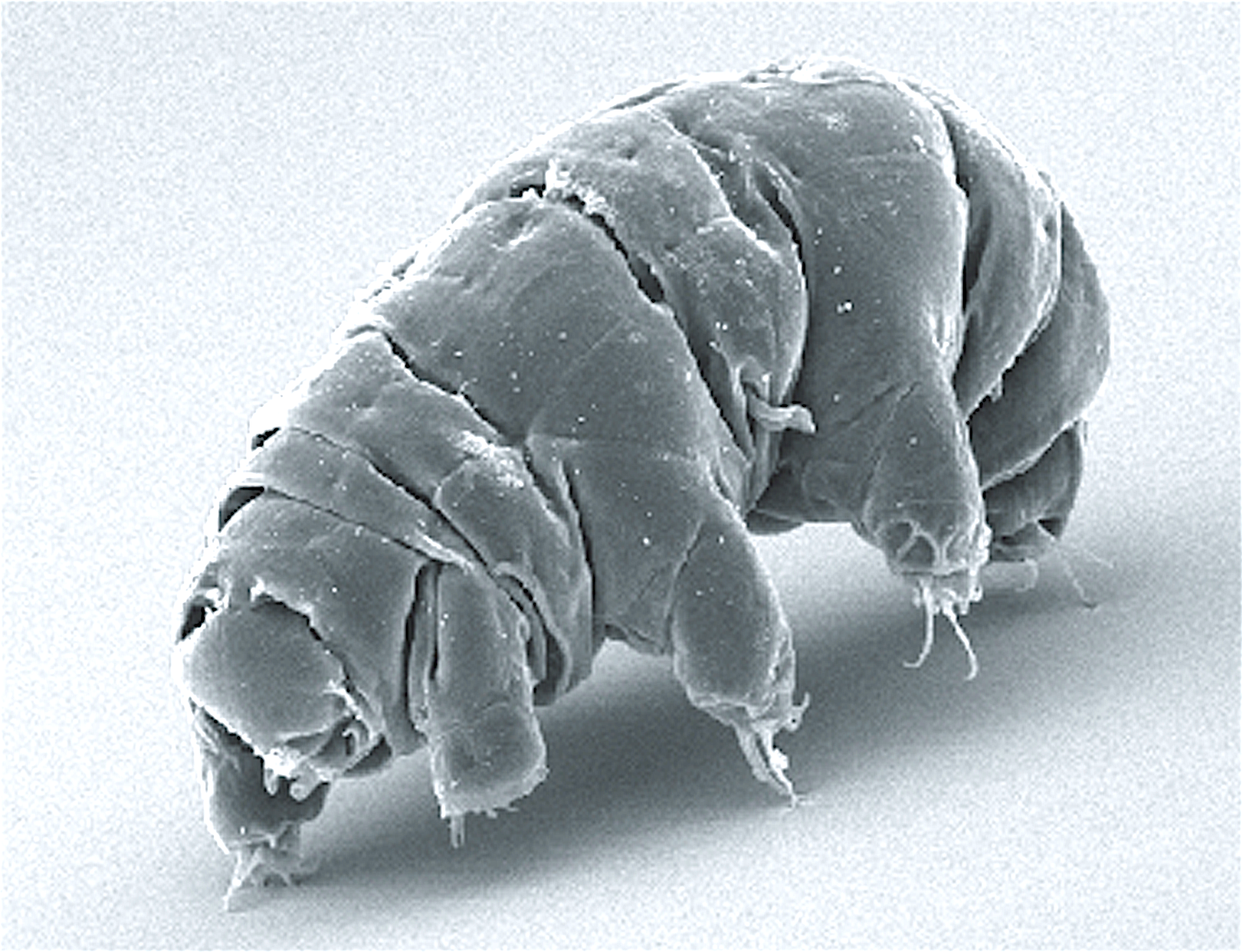

Tardigrades, or water bears, are tiny creatures, measured in microns, that live in the leaf litter and upper layers of soil. They’re called water bears because they have four pairs of stumpy legs with claws and also a conical snout. They eat plant residue and have stylets they use to pierce plant and animal cell walls and suck out the contents. They may also occasionally eat nematodes and rotifers.

Water bears need moist environments, and when things dry out, they can build a cyst around themselves, drop all activity to zero and just wait it out, sometimes for decades. They are also able to survive extreme heat and cold, including being boiled or dunked in liquid nitrogen. These survival tactics help them live through extreme droughts, heat and cold and revive when conditions improve. They’ve been taken on space flights and survived gamma rays and the vacuum of open space.

Rotifers are another category of microscopic aquatic soil dwellers. They live in films of water that stick to clumps of soil, or on lichens and mosses. They have cylindrical or spherical bodies with a ring of tiny hairs or cilia that they use for locomotion or to direct food into their mouths. They eat bacteria, fine particles of organic material, and smaller protists. Some species use their cilia to grind residues, pierce the cells of plants and fungi, and to capture protists and bacteria. They are particularly fond of places with lots of bacteria like manure heaps, compost piles and cow dung.

All of these tiniest of creatures carry on the same activities as tigers or whales. They hunt for food. They reproduce. They play specific roles in the environment of healthy soils, and they have no idea that we exist.

Photo by Schokraie E, et al. Alt text: Fat, worm-like tardigrade with 8 stubby legs, imaged with an electron microscope.

2 comments

Nematodes are amazing! This one was recently revived after 46,000 years frozen in the permafrost: https://www.npr.org/2023/07/30/1190950660/nematode-worm-permafrost-discovery-frozen

I saw that! And it lived its normal life span of two weeks after they thawed it out. Seems metaphysical somehow…